My Early Relationship With Prayer

There’s a deep ache that settles in the soul of someone who longs to be close to God, but finds prayer elusive. By elusive, I don’t mean absent—just hard to hold onto. Slippery. Like mist in the morning air.

That’s been my experience for much of my life.

I was born and raised into the home of a pastor. I was lucky enough to have two loving, godly parents who wonderfully modeled what it looked like to live as followers of the way.

From a very early age I remember loving God, and wanting to pray like my parents did.

However, there was a problem: my mind could not handle stillness. It was always racing with thoughts and wild imaginations.

I have vivid memories of a specific night when, as a boy, I knelt beside my bed with the sincere desire to pray, only to find my mind hijacked by technicolor visions of Super Mario Bros. 3.

The raccoon suit. The music. The warp whistles.

They flooded my imagination, uninvited but persistent.

I would feel confused and a little ashamed. Why couldn’t I focus?

Why couldn’t I pray like the people in the books?

I didn’t know it then, but my brain was working with an undiagnosed case of ADHD—a mind wired not for stillness, but for movement, curiosity, and endless rabbit trails.

It’s hard to be still and know God when your mind is racing.

Growing In Age, But Struggling In Prayer

Years later, when I stepped into pastoral ministry, the struggle didn’t disappear. In fact, it deepened.

I’d read biographies of great saints and mystics—men and women who spent hours in prayer, who woke at dawn to seek God’s face, who battled demons and interceded for nations.

Their prayer lives were painted as mountains of spiritual discipline and intimacy, and in comparison, mine felt like a molehill of failure.

On the one hand, I loved meeting God in intellectual pursuit.

I could read theology for hours. I could teach nuanced eschatology, dive deep into kingdom ethics, and hold students’ attention for multi-hour classes.

But when it came time to simply talk to God alone in a room, my eloquence dried up. My mind drifted.

My prayers felt small. Simple. Incomplete.

And that, somehow, felt like a betrayal.

I assumed prayer should rise to meet the depth of my study.

If I was capable of complex thought, shouldn’t my communion with God reflect that same sophistication?

If I could diagram Jesus’ teachings in the Sermon on the Mount, shouldn’t I be able to offer prayers that thundered like the Psalms?

There were times, of course, when the depth came. Usually in moments of crisis or compassion—praying over a student who was hurting, or interceding during a church service.

There was a sincerity in those prayers that wasn’t performance, but it was still... contextual. There was a rhythm, a structure, an audience.

Something to pull me into focus.

Alone, in the quiet, I floundered.

On the Curious Difficulty of Simple Devotion

And then—I became a father.

Having a child rewired every part of my life.

My schedule dissolved into fragments. My energy was scattered across a thousand needs.

And the space I once had for quiet reflection—lighting candles, walking into the woods, journaling with a cup of coffee and a Moleskine—vanished almost overnight.

I didn’t resent it. But I did feel like my prayer life, already struggling to breathe, had finally drowned.

And yet, strangely, it was in that place—bone-tired, overcommitted, surrounded by noise and need—that something sacred began to grow.

A seed I didn’t plant. A rhythm I didn’t plan.

It began with burnout.

A season of emotional exhaustion and spiritual disillusionment that forced me to slow down and ask for help.

I began meeting with a spiritual director, and he handed me a small sampling of the works of Thomas Merton.

I didn’t understand all of it at first, but one image struck me like lightning:

“A tree gives glory to God by being a tree.

For in being what God means it to be it is obeying God. It “consents,” so to speak, to God's creative love.

It is expressing an idea which is in God and which is not distinct from the essence of God, and therefore a tree imitates God by being a tree”

― Thomas Merton, New Seeds of Contemplation

Not by striving. Not by preaching. Not by achieving spiritual benchmarks.

But simply by existing as what it was created to be.

That thought undid me in the best way.

Because somewhere along the way, I had started believing that I needed to pray like someone else.

I kept trying to jam my awkward, restless, overthinking, creative self into the mold of the “prayer warrior” ideal—quiet, still, poetic, perfectly attentive.

But this image—this tree—whispered a different truth:

God didn’t want me to be someone else in order to meet with Him.

He wanted me.

Me with my distracted brain and burning heart.

Me with my audio Bibles and whispered prayers over sudsy sinks.

Me with my restless hands, my bursts of inspiration, my search for humble theology, and my stammering, childlike pleas for help.

I started to believe, for the first time in years, that I could connect with Him in the way He designed me to.

That He wasn’t frustrated by how I prayed.

He formed me. He understood the circuitry. He knew the rhythms that grounded me, the spaces that opened me up, the odd little rituals where my heart finally slowed down enough to hear Him.

And that changed everything.

I stopped trying to pray like a statue.

And I started learning to pray like a tree.

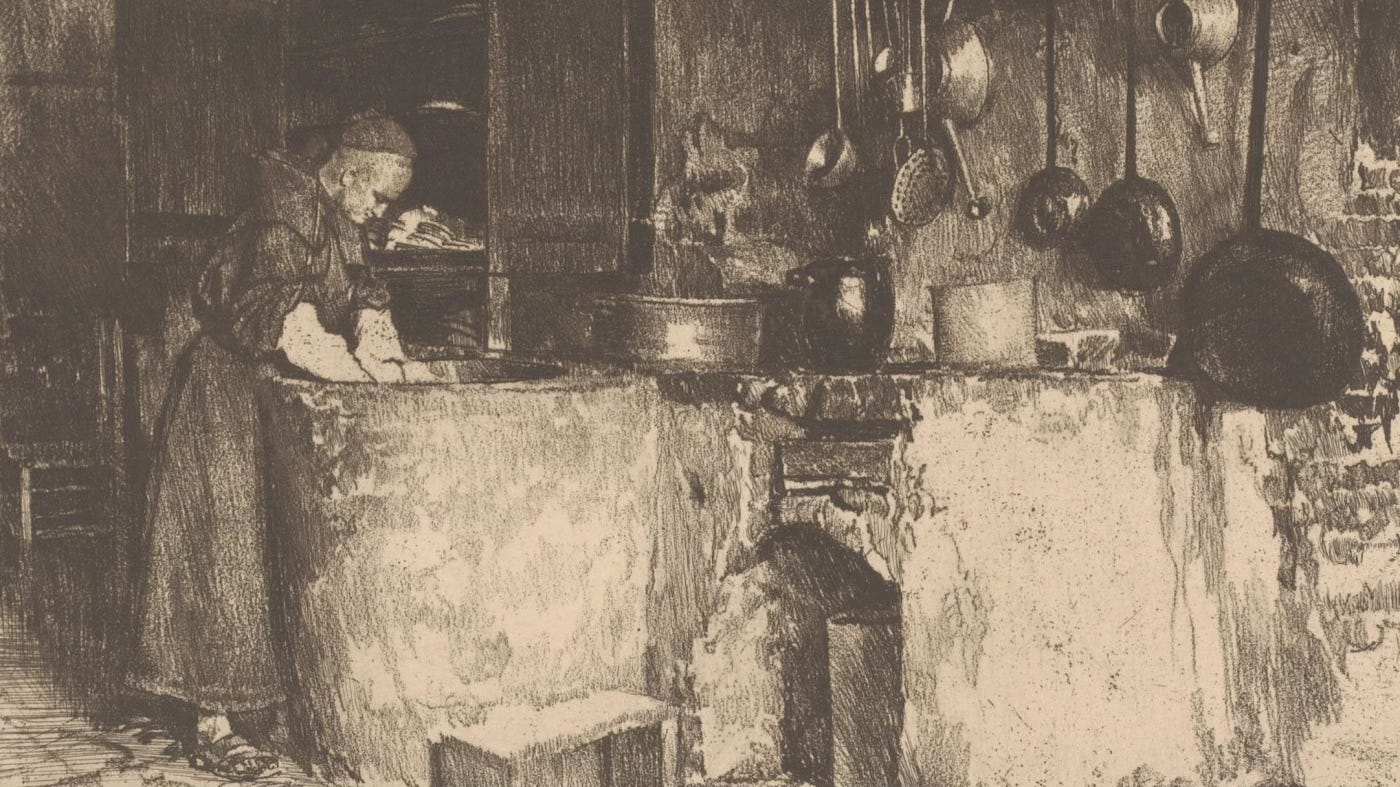

The Unexpected Theology of Dishwater

Around the same time, my wife—very pregnant, very tired—asked if I could be more present in practical ways around the house.

I’m not naturally drawn to chores (surprise, surprise?)

Dishes, in particular, have always felt like the bane of my domestic existence.

But something in me wanted to say yes.

Not just for her sake.

For mine.

So I started doing the dishes every night.

Right away, I saw something shift in me. Because for the first time in a long time, I was engaging in a daily rhythm that didn’t revolve around my phone or laptop.

Being at the sink forced me to work with my hands, stand in one place, and remain still for a longer period of time than I am usually still.

And somewhere in the silence, I began to notice the presence of God.

It wasn’t dramatic. There were no visions. No tongues of fire. Just stillness. And in that stillness, a whisper: I am here.

Sometimes I’d put on soft worship music. Sometimes an audio Bible or devotional. Sometimes nothing at all.

I’d find myself pausing and offering prayers that were so short, so simple, they felt almost childish.

“Thank you for today.”

“Please help me.”

“Be with Jack.”

”Help my students see you.”

“Give grace to my wife.”

“Please provide.”

“Let Your kingdom come in this house.”

They were not poetic. They were not profound.

But they were true.

And something in me began to heal.

It reminded me of something my Grandfather, Papa Tony, used to say, in that slow, wise voice he saved for holy things:

“Practice the presence of God.”

It can be a hard phrase to grasp. It can sound like something monks would say in stone chapels, not something for tired dads with aching backs and a sink full of spatulas.

But as my hands moved through the water and my mind unclenched from the day, I started to see what he meant. It wasn’t about conjuring some mystical state—it was about awareness. Attentiveness.

A posture of the heart that says, He is here, even now.

That phrase—practice the presence—eventually led me to Brother Lawrence, the humble friar with the holy audacity to meet God not in a cathedral but over a pile of dirty pots.

His words hit me like a benediction I didn’t know I needed:

“The time of business does not with me differ from the time of prayer; and in the noise and clatter of my kitchen... I possess God in as great tranquility as if I were upon my knees at the Blessed Sacrament.”

-Brother Lawrence

Sacred presence in the clatter.

Glory in the grease.

God in the ordinary.

When God Prefers You Unedited

I started realizing that Jesus was never waiting for my prayers to sound like my sermons.

He wasn’t disappointed that I didn’t speak to Him like Karl Barth.

He wasn’t looking for rigor—He was looking for relationship.

He just wanted me. Not the polished version.

Not the theological strategist.

Just the son. The friend.

And so I kept praying. In the car. While changing diapers. While washing dishes.

My life became scattered with tiny moments of surrender.

It didn’t feel like prayer in the classical sense. But it was prayer.

And slowly, I began to rediscover a truth I learned long ago—what Paul meant when he said, “pray without ceasing.”

It doesn’t mean never leaving your knees.

It means never leaving God.

These days, I still struggle to focus. Still drift.

Still wonder if I’m “doing it right.”

But I no longer carry the same weight of shame. I’ve stopped trying to make my prayers perform. I’ve stopped waiting for ideal conditions. I’ve started welcoming God into the mess.

Into the dishes.

Into the tired parenting.

Into the silent drives and interrupted thoughts.

And there, in the ordinary, I have discovered something extraordinary:

The God who speaks in burning bushes and clouds of glory also meets me at the kitchen sink.

The God of theologians and prophets and mystics also delights in my simple prayers, whispered over soap and ceramic.

And that is enough.

So well delivered. To go off of your Thomas Merton quote, I love this story, as delivered by Dale G. Renlund:

“Consider this insight provided by the 18th-century Hasidic scholar Zusya of Anipol. Zusya was a renowned teacher who began to fear as he approached death. His disciples asked, “Master, why do you tremble? You’ve lived a good life; surely God will grant you a great reward.”

Zusya said: “If God says to me, ‘Zusya, why were you not another Moses?’ I will say, ‘Because you didn’t give me the greatness of soul that you gave Moses.’ And if I stand before God and He says, ‘Zusya, why were you not another Solomon?’ I will say, ‘Because you didn’t give me the wisdom of Solomon.’ But, alas, what will I say if I stand before my Maker and He says, ‘Zusya, why were you not Zusya? Why were you not the man I gave you the capacity to be?’ Ah, that is why I tremble.”

This is such a wholesome depiction of God’s nearness and our distraction. The kitchen sink is one of my favorite places to talk with Him too. He does a lot of decluttering of the human heart in mundane tasks, I think.